From Carts to Charts: Instacart Files for IPO

In the world of marketplaces, groceries dominate.

The term ‘IPO’ is often associated with optimism. Even in an uncertain economic landscape, Instacart's decision to go public isn't just a significant moment for the company - it's a promising sign for marketplace startups and the broader tech ecosystem.

Instacart’s Journey

When Apoorva Mehta founded Instacart in 2012, most people weren’t considering a digital revolution in grocery shopping. Grocery stores seemed to be one of those immovable, 'real-world' industries—like hair salons or dentists—that wouldn't migrate to an app. But Apoorva saw a problem space that was ripe for disruption. He realized that grocery shopping was universally considered a chore, yet it couldn’t be easily outsourced because of the need for personal selection and immediate delivery.

Apoorva and his team seized upon an idea that has since dramatically reshaped how we think about grocery shopping - could a few taps on a smartphone replace the annoying act of combing through aisles? And with that, Instacart was born.

If you're in the startup world, you're likely familiar with the early struggles almost every company faces: proving market fit, establishing supply chain logistics, securing funding, and convincing customers that your solution is not just novel but necessary.

Instacart faced these challenges and more. Initial skepticism surrounded the idea, with concerns about scaling a business based on unpredictable shopping behavior. Consumers are fickle and influenced by external factors like holidays, weather, and current events. Shopping preferences can also vary from one location to another, complicating scale across different geographic areas. What works in a metropolitan area may not work in a rural setting, requiring a more nuanced GTM approach.

Furthermore, unlike other marketplace models where the product or service is relatively uniform (e.g., ride-sharing or hotel bookings), grocery shopping covers a wide range of products, from perishables to household items. Managing this variety while ensuring quality and timely delivery is an operational challenge.

But Instacart tackled these issues head-on, growing from a fledgling startup to a nationwide phenomenon in just a few years. It began by securing partnerships with key grocery chains, like Costco and Kroger, before expanding into convenience stores and adding multiple verticals to its offerings. The Company launched an "Instacart Express" subscription service to drive recurring revenue and encourage customer loyalty. And let’s not forget how it scaled its operations at the onset of the pandemic - when physical stores became war zones of potential infection, Instacart rapidly expanded its workforce to meet soaring demand.

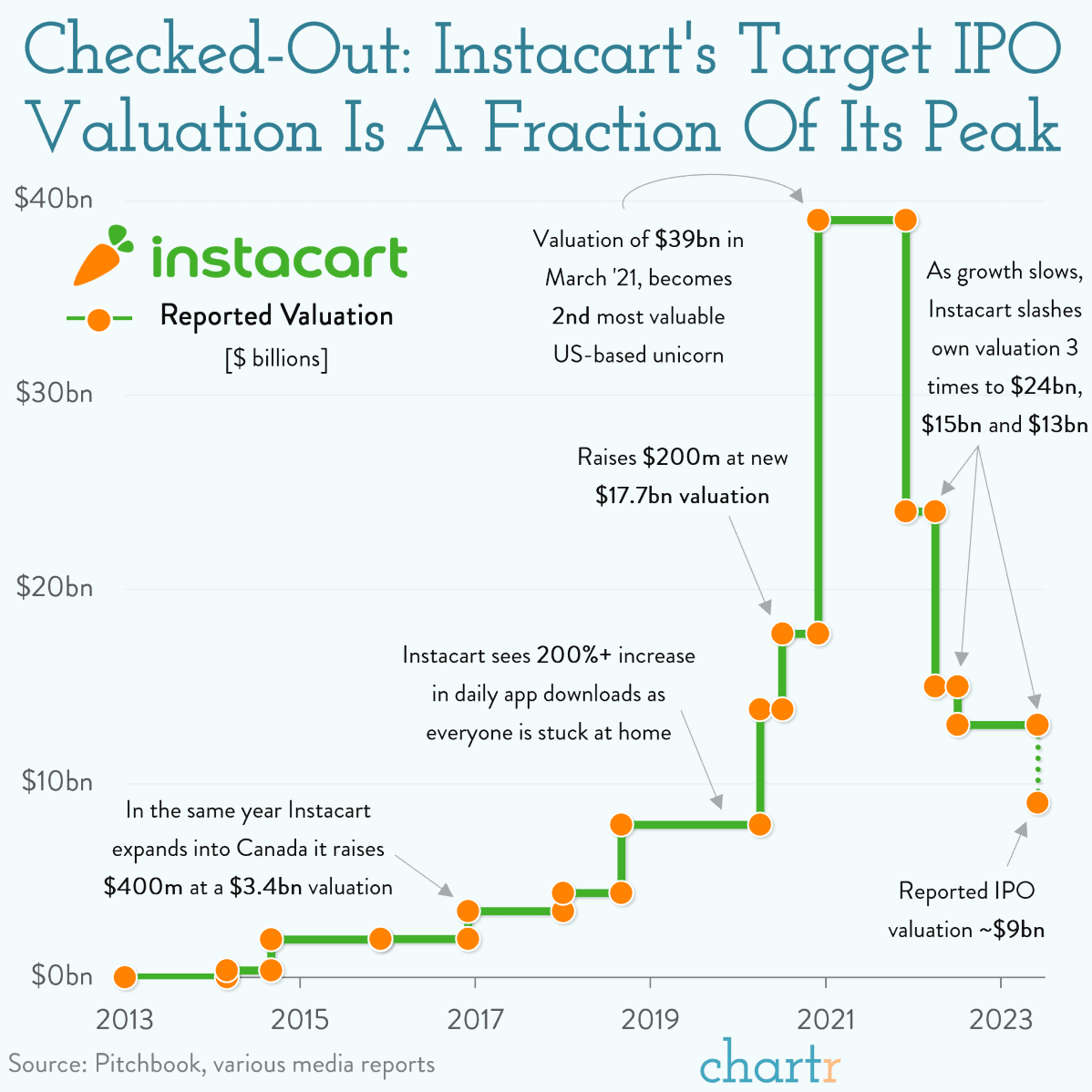

The result? Here we are, nearly a decade after its inception, and Instacart is about to go public, targeting a $9bn valuation. It’s a far cry from its peak valuation of $39bn, but it shows the ability to dominate a space that many thought was impenetrable for digital disruption.

The Business Model that Delivers

I love companies that, on the surface, appear to be one thing but, when you dig deeper, reveal that their success comes from something completely different. It likely comes from the early stages of product-market fit, going to market with an initial business model to realize that new verticals are more profitable than the first.

Take Amazon, for example. The Company is an online retail giant, but most of its profits come from Amazon Web Services (AWS), its cloud computing division. AWS has consistently been a high-margin business compared to the razor-thin margins in retail. Or Microsoft, the gaming console maker, that makes more money from licensing fees and Xbox Live subscriptions. Or LinkedIn, where the social network draws professionals in, but the real money comes from helping companies hire those professionals.

At first glance, Instacart's business model might seem simple - a DoorDash but for groceries. But to simplify it to that would be to overlook the complexity that makes this marketplace so genius.

So, what's the secret sauce? Instacart does not own the inventory it delivers, a conscious business decision that dramatically reduces overhead. Traditional grocery stores struggle with stock, which depreciates at an alarming rate because much of it is perishable. Instacart sidesteps this by simply being a bridge between consumers and retailers, capitalizing on their existing infrastructure.

Instacart’s S-1 filing shows another example of this ingenuity. Underneath the surface, Instacart is an ad business that happens to sell groceries. The company did $740 million in advertising revenue in 2022, nearly a third of its total revenue.

In this ecosystem, ‘shelf space’ is now virtual. Big brands like Pepsi and Hershey aren't just fighting for prime real estate in a cluttered supermarket aisle - they're vying for your attention at the top of your Instacart search results.

When you type "granola bars," it's no accident that Chewy often emerges as the top pick - this is a strategic decision made by the company. The same way third-party vendors pay for placement on Amazon, the same way publishers pay for clicks on Google.

And here's where it gets fascinating: Instacart has cleverly inverted the traditional model. Instead of its core service - grocery delivery - being the profit center, it's increasingly taking on the role of a loss leader. The golden goose lies in its ability to offer something even more valuable to brands: visibility and conversion.

By leveraging its platform to sell 'virtual shelf space,' Instacart isn't just making a quick buck - it’s generating high-margin revenue that can be cycled back into subsidizing its more capital-intensive logistics operations. That explains why Instacart has raised only $2bn in venture funding compared to Uber’s $25bn.

Another aspect that goes overlooked is data. Instacart collects valuable data about shopping behaviors, preferences, and seasonal trends by sitting at the intersection of consumers and groceries. This data is not merely descriptive; it's predictive. It can guide inventory decisions for retail partners, optimize delivery routes, and even influence the development of private-label brands. The opportunities are endless.

So, what we're looking at is not just a grocery delivery service but a complex, multifaceted marketplace. A place where delivery acts as a form of lead generation, paving the way for an advertising model that’s more robust than it appears.

It's as if Instacart has engineered a stealthy profitability engine under the label of a delivery service, creating network effects that drive future growth.

The lesson here? Brands will follow consumers, and they will pay to play. A mature business with unique data is precious to advertisers and a key way to establish an advantage (as long as the underlying transaction volume drives advertisement demand).

Unrivaled GMV Dominance

The business model makes Instacart a great company, but its adaptability makes it an absolute force. The marketplace model is inherently flexible, allowing the company to pivot quickly to meet the changing needs of consumers. During the pandemic, when foot traffic to grocery stores dropped dramatically, Instacart ramped up its services and offered new features like contactless delivery and bulk purchasing options.

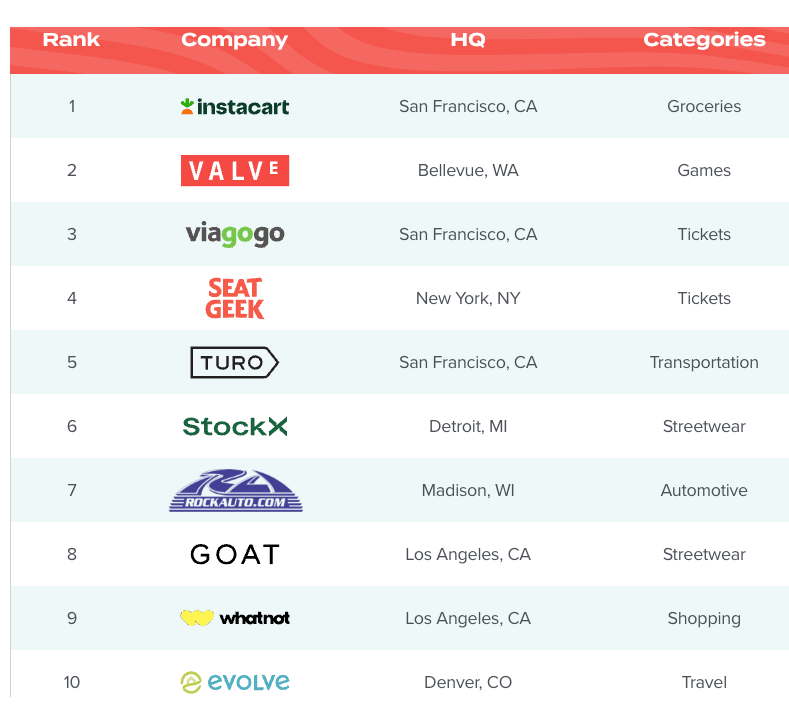

This agility is not by chance - it's built into the DNA of its business model, making it resilient to fluctuations in consumer behavior and broader economic conditions. And this agility can explain why Instacart has ranked #1 in Gross Merchandise Value (GMV) across all private marketplaces for the last three years. Yes, that includes verticals as diverse as shopping and travel, not just the grocery aisles.

In fact, if we zoom out and evaluate the Top 100 private marketplaces, Instacart makes up a whopping 71% of the entire group’s GMV. No other grocery company even cracks the list.

As shown above, with tickets and shopping, not all verticals see this dominance. Groceries have specific characteristics that lean towards a "winner-takes-all" dynamic, especially across marketplaces. First, grocery shopping is a habitual activity. Once consumers find a service that meets their needs, they're less likely to switch - this inertia benefits the market leader. As more customers use Instacart, more suppliers/brands want to partner with them, attracting even more customers. This cycle reinforces itself and creates a strong network effect. Other marketplaces that benefit from this include weddings (Zola), cannabis (Eaze), online auctions (eBay), and collaboration software (Slack).

This dynamic is important, as it determines whether an industry can support many billion-dollar companies or a few. Investing in a "winner-takes-all" market involves identifying the likely winner early. Once a company establishes a dominant position, it often becomes a safer, albeit more expensive, bet.

Key Takeaways

In a world that increasingly tips towards network effects and economies of scale, marketplaces like Instacart are a fascinating study of strategic genius.

Companies like these don't just deliver a product - they deliver an ecosystem of consumers, suppliers, and data, all connected to form a moat against competition. Instacart's dominant position is a testament to the power of leveraging a traditional industry like retail through innovative tech, logistics, and a business model that adapts to supply and demand.

If there's one thing to take away from its story - modern entrepreneurship isn't just about inventing something new; it's also about understanding the structures of existing markets and finding scalable, even disruptive, ways to extract untapped value. In doing so, Instacart isn't merely surviving the cutthroat landscape of tech startups; it's shaping the future of how we think about commerce, retail, and technology itself.

Cheers for reading.

Great post!